Across the social impact landscape, we are seeing organizations look at an old question with fresh eyes:

Is this work ready to spin off into its own entity?

This question is often triggered by a program starting to gain its own center of gravity, growing a coalition, network, or collective impact model that tests or stretches the strategy, theory of change, or scope of the parent organization.

For a long time, that question was framed almost entirely around readiness: Is there leadership capacity? Can it manage its own board, funders, and operations? Is the work mature enough to stand alone?

Those questions still matter, but increasingly, organizations we work with from economic development to youth development to food systems are pairing them with another one that addresses the resource-constrained environment we are in: Does this work create more strategic value together or apart?

From “Stages” to “Models”

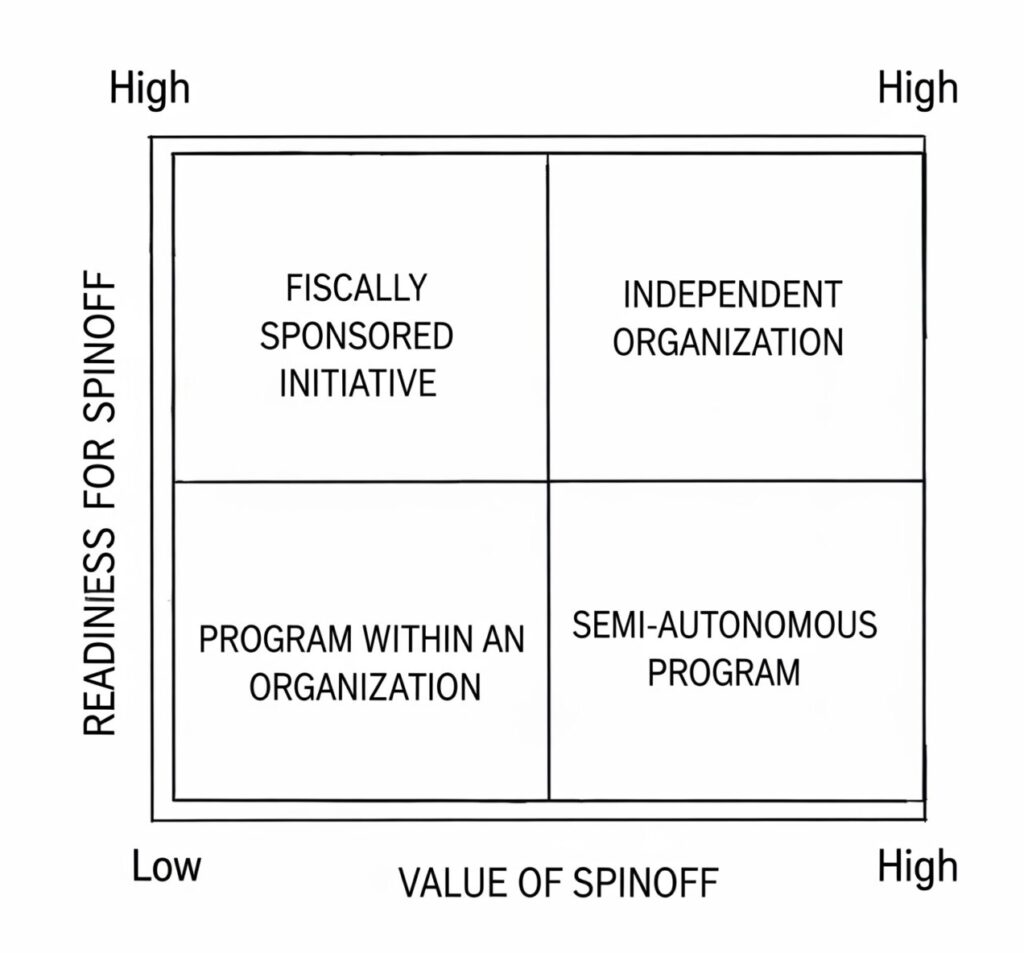

Most organizations recognize that initiatives evolve through different stages of relationship to a parent organization, from internal programs, to semi-autonomous efforts, to fiscally sponsored initiatives, and sometimes to full independence. Rather than treating them as a one-way path toward independence, they’re using them as strategic configurations: models to be revisited as the work and the system evolve.

This is especially true for collective and coalition work, which often starts as a program for its speed and legitimacy. As networks from around the momentum, a program can become its own animal, requiring a different governance posture.

Model 1: Program within an Organization

Lower readiness | High strategic value of integration

Fully embedded programs are often the starting point, particularly when work needs to move quickly, leverage an existing brand, or operate under a trusted institutional umbrella. In this configuration:

- Strategy, budget, and staffing sit with the parent

- There is no separate governance body; the parent board is the board

- Risk is fully absorbed by the parent organization

For many types of work, especially early collective efforts, this is a feature, not a bug. When coordination demands increase, external relationships multiply, or the work begins to require its own strategic voice, staying fully embedded can become a bottleneck rather than a support.

Model 2: Semi-Autonomous Program

Growing readiness | High strategic value of integration

Semi-autonomous programs often emerge when work outgrows simple program management but isn’t yet ready for, or doesn’t yet need, legal separation. Here we typically see:

- A clearer identity and strategy

- An advisory or steering group

- Greater leadership autonomy

- Continued fiduciary control by the parent

This is a deliberate middle configuration, not a holding pattern. For many backbone and collective efforts, this is the stage where complexity shows up fast: more partners, more funders, more expectations for neutrality and coordination.

The key question here is whether more autonomy could meaningfully improve credibility or impact, without major risk to the parent. Sometimes, this is the point where fiscal sponsorship becomes strategically necessary.

Model 3: Fiscally Sponsored Initiative

High readiness | High strategic value of integration

This is one of the most powerful and most misunderstood models. Fiscally sponsored initiatives are legally distinct, often with their own governing body and leadership, but remain financially housed within a sponsor that manages fiduciary risk.

We’ve supported many initiatives at this stage that could be fully independent, but intentionally are not.

Why? Because integration still creates value:

- Shared accountability and risk management

- Stronger system-level coordination

- Credibility with diverse stakeholders

- Reduced administrative overhead

For systems and backbone work especially, this configuration allows the initiative to lead its own strategy, networks, and partnerships while preserving the benefits of connection.

Here, independence is not the default next step.

Model 4: Independent Organization

High readiness | Lower strategic value of integration

In some cases, full independence becomes necessary to achieve long-term goals. This is most often true when:

- The work requires its own fiduciary board and networks

- Distinct revenue models or compliance needs emerge

- Autonomy enables sharper accountability or growth

In this configuration, the parent organization becomes an optional partner rather than a governing home.

This is the clearest case for a spin-off — not because independence is a marker of success, but because it directly strengthens the work’s ability to deliver impact.

What Two Decision Axes Make Possible

The upshot of all of this is not just that spinoffs become intentional vs inevitable, integration is viewed as a source of value, rather than a lack of maturity, and that collective impact work is scaffolded and supported.

It’s that organizations zooming out to look at their governance model are able to maximize the outcomes of their collective bodies of work, maximizing impact for the public good.